Septic Mandate Showdown: Florida’s Unfunded Deadlines Hit Home

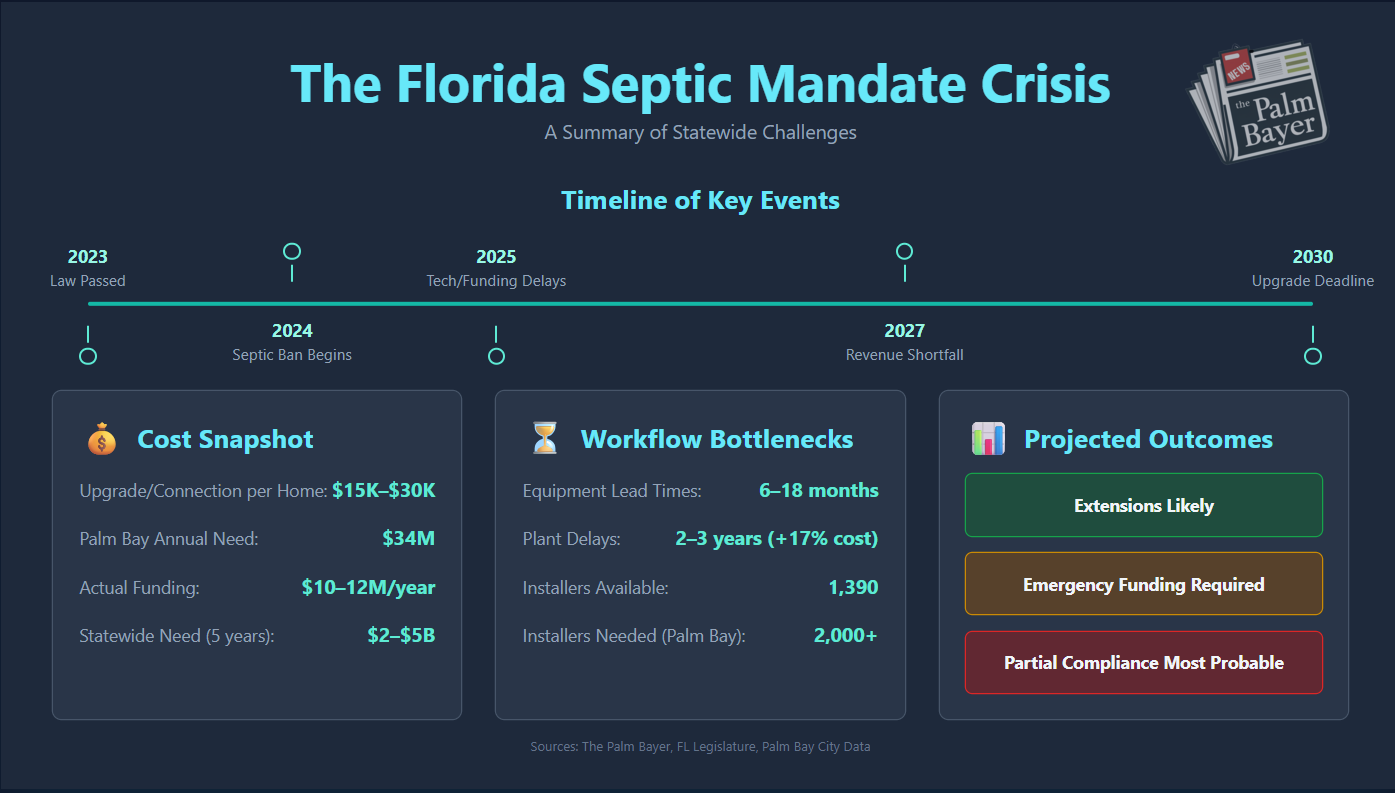

Florida faces a 2030 septic mandate with no funding extension, leaving cities like Palm Bay in a costly race that could raise utility bills and taxes statewide.

Palm Bay, FL: Whether your home still relies on a septic system or you’re already connected to city utilities, the next few years will bring a shared reckoning. Florida’s septic mandate set a 2030 deadline the state still isn’t equipped to meet (as I first reported in January 2024 in Florida’s New Septic Mandates: What You Need to Know). Nearly two years later, the same obstacles remain, with only four years left on the clock—and the financial fallout is poised to land squarely on local taxpayers and utility customers alike. This isn’t just another policy update; it’s the moment where prediction becomes reality.

Why It Matters to Everyone

Two years after my January 2024 report on Florida’s septic mandate, little measurable progress has been made, and only four years remain to comply. This continuation shows how the issues once forecast are now pressing realities.

Even households already hooked to sewer lines aren’t insulated from what’s coming. Every septic conversion requires new mains, treatment capacity, and maintenance staff, and Palm Bay Utilities can’t shoulder that expansion alone. With the city’s charter limiting property tax increases and state funding covering only a fraction of costs, the missing dollars can come from just two places: higher monthly utility bills or local taxes.

In short, the city may not ask if it can afford compliance, but how residents will fund it. The pipes and plants are public assets, and public assets draw on public wallets.

The Mandate Without the Money

State law still says every property in Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP) zones must upgrade or connect to sewer by 2030. Yet no legislation has extended that deadline, no new funding stream has been approved, and no workforce surge is on the horizon.

Cities like Palm Bay face a task that grows more expensive each month. Equipment lead times now stretch a year or more, costs are up double digits, and even with recent grants, the city’s annual funding gap sits near $24 million. For local governments, it’s like being told to finish a marathon before the starting gun—with no shoes, no water, and a clock already ticking.

The law demands results that the math can’t support. Florida’s environmental policy has become a promise written on an empty check.

Palm Bay’s Race Against Time

Palm Bay’s wastewater master plan calls for $375 million in plant and line upgrades, but major projects like the South Regional Water Reclamation Facility remain delayed and over budget. ARPA funds have helped a handful of homeowners connect, and new grants will aid a few hundred more. But at the current pace, fewer than half of the city’s priority-area systems could be addressed before 2030.

Meanwhile, nitrogen runoff continues to feed the Indian River Lagoon’s decline, drawing more regulatory pressure from the state and federal level. The city is complying, but compliance without cash can only go so far.

Supply Chain and Workforce Capacity Crisis

Beyond funding, Florida faces an equally daunting logistical challenge. Equipment shortages, inflated costs, and a limited workforce have made timely compliance nearly impossible.

Supply Chain Strain

Critical components such as pumps, valves, and electrical systems now have lead times exceeding six months. Palm Bay’s South Regional Water Reclamation Facility exemplifies the issue. The project has faced delays of up to three years and cost overruns exceeding 17% due to unavailable equipment.

Advanced Treatment Units (ATUs) are the direct replacements for traditional septic tanks, using advanced nitrogen-reducing technology. These systems cost between $15,000 and $30,000 for a typical three-bedroom, two-bath home. Distributed Wastewater Treatment Systems (DWTS) are small, neighborhood-scale treatment units serving clusters of homes where central sewer extensions aren’t feasible. Both technologies remain in short supply, creating a statewide backlog that threatens to derail conversion timelines and inflate costs further.

Workforce Shortage

Florida has roughly 1,400 licensed onsite sewage contractors, enough to handle fewer than 35,000 installations per year. Palm Bay alone needs about 2,000 conversions annually to meet the state’s schedule. That goal is far beyond current capacity. Training programs require multiple years, meaning meaningful workforce expansion isn’t expected before 2028.

Key Capacity Numbers:

Licensed contractors statewide: ~1,400

Statewide annual conversion need: 100,000+

Palm Bay annual target: 2,000 conversions

Earliest workforce recovery: 2028

These supply and labor constraints, combined with the funding gap, make compliance mathematically impossible by 2030 without major state or federal intervention. Each delay adds cost pressure. With every month of delay, costs escalate, and the pool of available contractors shrinks, making future compliance an even steeper climb.

What Happens Next: Four Futures for Florida’s Septic Mandate (with Likelihoods)

Phased Compliance (≈45%) – The state and cities make partial progress by focusing on high-priority areas first. Funding comes from emergency grants and piecemeal local projects, leaving many conversions delayed past 2030.

Legislative Extension (≈35%) – Lawmakers concede the deadline is unrealistic and extend it into the 2040s. They introduce new loan and grant programs, buying time but not solving the underlying funding shortage.

Federal Intervention (≈12%) – A major environmental event prompts EPA action. Federal emergency funds accelerate work, but cities lose some control over how and where projects proceed.

Mandate Collapse (≈8%) – Multiple cities challenge the law, prompting the Legislature to roll back or suspend the 2030 requirement. Conversions continue voluntarily through grants, but enforcement largely disappears.

No matter which of these paths Florida takes, they all share one outcome: someone will have to pay the bill.

That someone will be the residents, through higher rates, new fees, or general taxes.

Whether the money comes from the tap or the tax roll, it will come from the same place: your household budget.

Closing Reflection

While the 3% cap keeps government efficient, it also limits Palm Bay’s ability to respond quickly to unfunded state mandates like this, adding real tension between fiscal responsibility and practical necessity.

The mandate was written with good intent, to protect our waterways and the Indian River Lagoon. But without a realistic path to fund and staff the work, Florida’s cities are left trying to build infrastructure on promises alone.

Palm Bay isn’t resisting the law; it’s living within arithmetic. The city’s 3% property tax cap, a safeguard I’ve long supported, forces officials to be creative stewards of limited revenue. It constrains flexibility but also demands efficiency, a reminder that fiscal discipline and environmental responsibility must coexist.

As deadlines draw closer, every Floridian should understand this isn’t a question of if the costs arrive, but when, and how evenly they’ll be shared.

Looks like these State mandates can get a wee bit expensive. (At least the affected people allegedly live near a waterway, unlike most Palm Bay residents) Orlando Sentinel Dec 15, 2025

Facing big bill for waste

Replacing septic tanks near Wekiva could cost Seminole

homeowners thousands

{{{Articles.Byline.1}}}

Seminole commissioners were hit with a stunning dose of sticker shock this week after learning a state

requirement to convert most septic tanks near the Wekiva River and Gemini Springs to sewer systems could

cost the county and homeowners hundreds of millions of dollars.

For example, a homeowner with a septic tank near the Wekiva River could have to shell out at least $75,000 if

they had to pick up the entire cost of digging up their old septic tank and replacing it with a sewer connection,

according to a county document.

“I would say that a majority of our residents would not be able to afford to pay that, even if they went to the

bank and got a loan,” Commissioner Jay Zembower said. “None of us want to do that.”

Despite the costs, commissioners and county staff acknowledged that protecting the environmentally

delicate springs is critical. Old septic systems are major contributors to nitrogen and phosphorus polluting the

water bodies.

“I think we all agree that we all want to clean up the environment,” Zembower said. “We want to be kind to the

environment. We want to get the nutrients out of the water… But that comes with a cost.”

In Sweetwater Club — an upscale neighborhood developed in the mid-1980s just south of Wekiwa Springs

State Park — all 176 homes have septic tanks and are in the state-mandated conversion area.

“I would love to be connected to a sewer system. It’s something that should be done, especially because of the

environmental concerns,” Sweetwater resident Bahram Yusefzadeh said in his front yard Friday. “But I don’t

believe the average middle-class community could afford something like that. I don’t think you’re going to get

much support from most neighborhoods.”

Yusefzadeh added that such a project would involve tearing up his neighborhood’s streets and residential

yards. He recalled replacing his home’s septic tank about 15 years ago at a cost of more than $30,000 and

what an “expensive mess” it was.

Seminole commissioners blasted state legislators for enacting such a mandate without providing funding,

and leaving it up to local governments to figure out the costs.

“We can’t impose this on our citizens,” Commissioner Lee Constantine said. “It’s too big. It’s too large. So at

some point, the Legislature is going to have to bite the bullet and do what’s right. The state is going to have to

decide how to pay for it.”

Under the 2016 state law designed to protect Florida’s natural springs, the county has until 2038 to connect

septic systems on lots of up to an acre to sewer lines in designated areas within the Wekiwa Springs Basin or

Gemini Springs Basin. Or the county can require homeowners to upgrade their septic tanks to modern

systems that release fewer nutrients into the springs

The mandate wants to force me to connect to a utility even though my house is miles away from the Lagoon. Yet they are willing to entertain a daily industrial discharge directly into the Lagoon?

Florida Today Nov 28, 2025

Lagoon discharge permit sought

Blue Origin would treat industrial wastewater

Jim Waymer

Florida Today USA TODAY NETWORK – FLORIDA

Blue Origin is seeking a state environmental permit to discharge about 15,000 gallons daily of “industrial wastewater” used in rocket component testing, cleaning and cooling operations to an onsite pond that flows to the Indian River Lagoon.

What’s happening?

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection is preparing a draft permit to Blue Origin, LLC, to let Blue Origin operate a 490,000gallon-per-day industrial wastewater treatment plant that would discharge 15,000 gallons of wastewater to a 402,981-square-foot onsite stormwater pond, then to the Indian River Lagoon.

Where would this happen?

Blue Origin’s manufacturing site is at 8082 Space Commerce Way, Merritt Island, just east of Pine Island Conservation Area.

Why would this happen?

Blue Origin plans to use highly filtered water to test and clean rocket parts. Instead of sending the water to a sewer plant, the company wants to discharge it to the lagoon after it is diluted in the onsite pond.

What water quality parameters apply in this permit?

Oil and grease, pH, nitrogen, and phosphorus apply. Industrial wastewater includes water from manufacturing, commercial operations, cooling systems, and cleanup of chemical- contaminated sites.

If wastewater comes from an industrial process rather than toilets or sinks, it’s called industrial wastewater, even if it’s mostly water with mild contaminants.

What will Blue Origin have to do if it gets the permit?

Among other things: conduct continuous monitoring and sampling and ensure discharges don’t harm wildlife, human health, or violate water quality standards; follow a stormwater pollution prevention plan

How and when can I see the permit application?

DEP has issued a draft permit and plans to approve it unless public comments lead to changes. Anyone can submit comments or request a public meeting within 30 days of the public notice.

Final permit issuance is expected by late Dec. 2025.

The application file and supporting data are available for public inspection during normal business hours, 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday, except legal holidays, at DEP’s central district office, 3319

Maguire Blvd, Suite 232, Orlando, Florida 32803-3767, at phone number (407) 897-4100.

DEP intends to issue the permit unless as a result of public comment appropriate changes are made.

How do I provide comments or request a public meeting?

Submit written comments or written request for a public meeting to Randall Cunningham, 3319 Maguire Blvd, Suite 232, Orlando, Florida 32803-3767. Those requests must contain the information below and be received in DEP’s central district office:

● The commenter’s name, address and telephone number; the applicant’s name and address; DEP’s permit file number ( FL0A00007-002-IW7A); and the county in which the project is proposed (Brevard);

● A statement of how and when notice

of DEP’s action or proposed action was received;

● A statement of the facts DEP should consider in making the final decision;

● A statement of which rules or statutes require reversal or modification of DEP’s action or proposed action; and if desired, a request that a public meeting be scheduled, including a statement of the nature of the issues proposed to be raised at the meeting