Palm Bay Councilmember Sues City Over Meeting Rules

Lawsuit claims new council rules silence free speech; city response likely based on Supreme Court precedent

Introduction

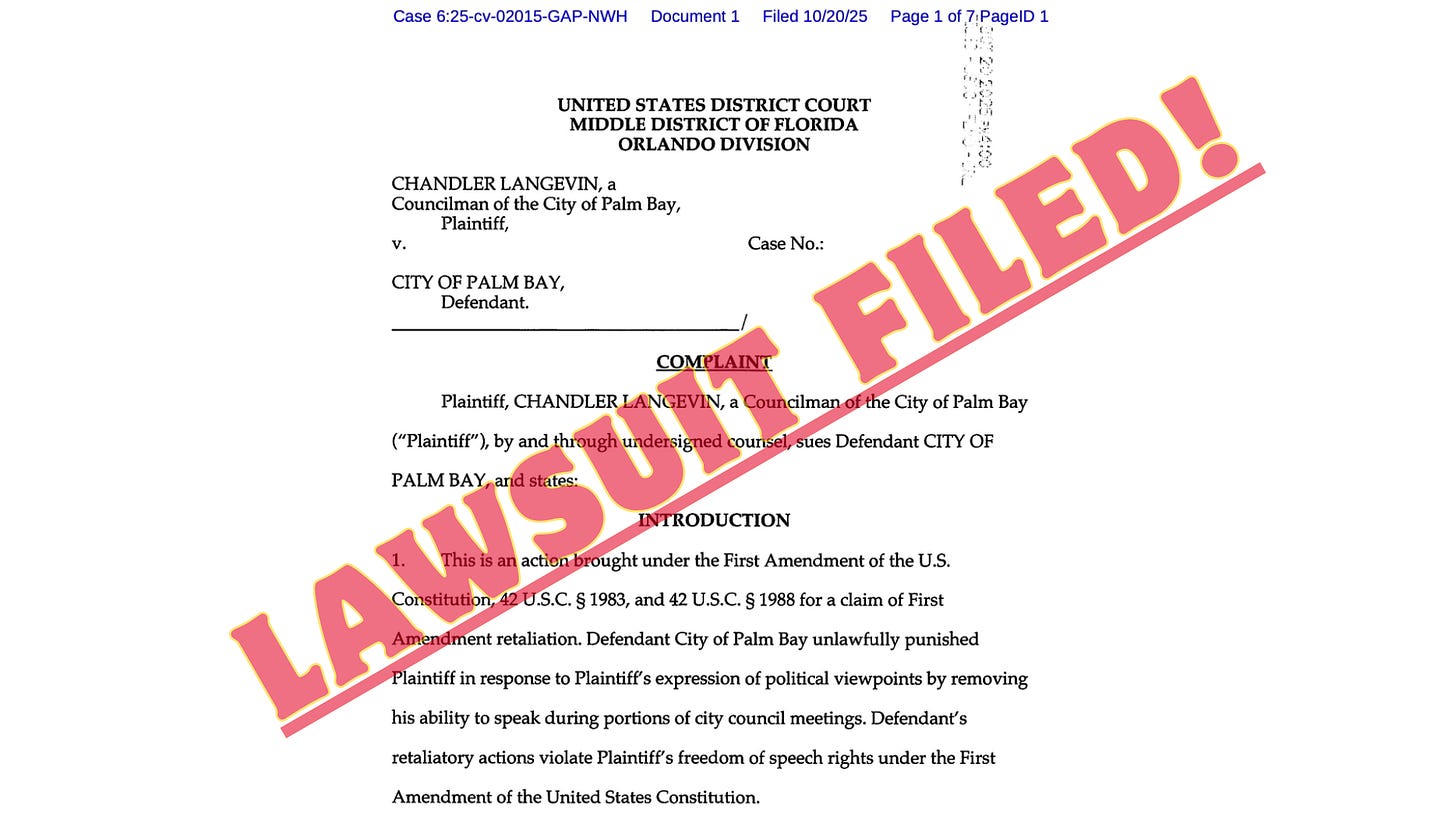

PALM BAY, FL - October 21, 2025 - A Palm Bay city councilmember has filed a federal lawsuit against the city, claiming that new rules limiting when council members can speak during meetings violate the First Amendment. Councilmember Chandler Langevin filed the lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida, arguing that the city’s procedural changes silence his voice and prevent him from representing his constituents.This case brings to light critical issues concerning free speech rights, governmental procedures, and the extent to which elected officials are bound by city meeting regulations. Beyond the legal arguments, the lawsuit raises questions about public trust in city government, Particularly when an elected official sues the very body they serve on.

Background

Councilmember Chandler Langevin filed the lawsuit against the City of Palm Bay in federal court on Monday October 20, 2025. The lawsuit challenges new rules adopted by the city council that changed when and how council members can speak during meetings. According to Langevin, these rules were specifically designed to limit his ability to participate in discussions and debates. He claims the rules prevent him from fully representing the people who elected him and violate his constitutional right to free speech under the First Amendment

These rule changes emerged from contentious council meetings that addressed censure motions and procedural reforms, highlighting the ongoing tensions that form the backdrop of this legal challenge.

The lawsuit names the City of Palm Bay as the defendant. Langevin is seeking a court order to stop the city from enforcing these rules and to declare them unconstitutional. He argues that as an elected representative, he has a right to speak on behalf of his constituents without unreasonable restrictions.

Langevin’s Claims

Councilmember Langevin makes several key arguments in his lawsuit. First, he claims the new meeting rules violate his First Amendment right to free speech. He argues that limiting when he can speak during council meetings prevents him from expressing his views and representing his constituents effectively.

Second, Langevin argues that the rules were created specifically to target him and silence his voice on the council. He believes the other council members passed these rules to stop him from raising certain issues or challenging their decisions.

Third, he claims that these restrictions harm not just him, but also the voters who elected him. When he cannot speak freely at meetings, his constituents lose their voice in city government. He argues that this undermines democracy and the public’s right to have their elected representatives participate fully in government discussions.

Langevin wants the court to declare the rules unconstitutional and order the city to stop enforcing them. He also seeks damages for the harm caused by these restrictionsAmong other things, Langevin is asking the court for an immediate order (preliminary injunction) and a permanent ruling to block the rules.

Likely City Response

The City of Palm Bay will likely defend itself by arguing that it has the legal right to set its own procedural rules for council meetings. Cities and other legislative bodies have broad authority to decide how their meetings are run, including when members can speak, how long they can talk, and what topics can be discussed at specific times.

The city will probably argue that the rules apply equally to all council members and are not designed to target Langevin specifically. They may claim the rules were created to make meetings more efficient, orderly, and productive, not to silence anyone’s speech.

Additionally, the city will likely argue that it is protected by legal immunity. Under established law, cities and their officials cannot be sued for damages when they are performing legislative functions like setting meeting rules. The city may also argue that individual council members who voted for the rules are protected by legislative immunity, which shields lawmakers from being sued for their votes and legislative actions.

Finally, the city may point out that Langevin still has opportunities to speak during meetings-just at specific times according to the new procedures. They will argue that reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions on speech are constitutional, especially in the context of government meetings that need structure to function properly.

What the Courts Say

Several important Supreme Court cases will likely shape how the court decides this lawsuit. Understanding these cases helps explain why Langevin’s lawsuit faces significant challenges.

In Houston Community College System v. Wilson, 595 U.S. 468 (2022), the Supreme Court ruled that a community college board member could sue for First Amendment retaliation when the board censured him for his speech. However, the Court made clear that the board member could only seek a declaration that his rights were violated and an injunction to stop future violations. He could not seek money damages from the college itself. This case suggests that even if Langevin proves his rights were violated, he may not be able to recover financial compensation from the city.

In City of Newport v. Fact Concerts, Inc., 453 U.S. 247 (1981), the Supreme Court held that cities and municipalities cannot be sued for punitive damages under Section 1983, the federal civil rights law. The Court explained that punitive damages are meant to punish and deter wrongdoers, but it doesn’t make sense to punish a city because that would ultimately harm innocent taxpayers. This case means that even if Langevin wins, he cannot seek punitive damages from Palm Bay.

In Bogan v. Scott-Harris, 523 U.S. 44 (1998), the Supreme Court ruled that local legislators are absolutely immune from being sued for damages for their legislative activities. This means that individual council members who voted for the new rules cannot be sued personally, even if those rules are later found to be unconstitutional. The Court explained that this immunity is necessary to allow legislators to do their jobs without fear of constant lawsuits. While this case deals with individual legislators rather than the city itself, it shows how strongly the courts protect legislative decision-making from lawsuits.

Together, these cases create a legal framework that makes it very difficult for elected officials to successfully sue their own legislative bodies over procedural rules. The courts generally give wide latitude to legislative bodies to manage their own affairs.

Challenges for the Lawsuit

Langevin’s lawsuit faces several significant obstacles that make it difficult to win.

First, the case law strongly favors the city. As explained above, courts have consistently held that legislative bodies have broad authority to set their own procedural rules. Unless Langevin can prove that the rules completely prevent him from speaking or were created with discriminatory intent, the courts will likely defer to the city’s judgment about how to run its meetings.

Second, Langevin will have difficulty proving that the rules were specifically designed to target him. If the rules apply equally to all council members, the court may view them as neutral procedural requirements rather than unconstitutional censorship. The city will argue that all council members must follow the same rules, which undermines Langevin’s claim that he is being singled out.

Third, there may be factual contradictions in Langevin’s claims. If the record shows that he still has opportunities to speak during meetings, just at designated times, it will be hard to argue that his speech is being completely silenced. Courts recognize that some procedural structure is necessary for meetings to function, and reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions are generally constitutional.

Fourth, even if Langevin can prove his First Amendment rights were violated, his remedies are limited. Based on the Houston Community College case, he likely cannot recover money damages from the city. At most, he might obtain a court order declaring the rules unconstitutional and requiring the city to change them. But this limited remedy may not be worth the time and expense of federal litigation.

Finally, the lawsuit could face procedural challenges. The city may argue that Langevin lacks standing to sue, or that the case is not yet “ripe” for judicial review because he has not exhausted all available remedies within the city’s own procedures. These technical legal issues could result in the case being dismissed before the court ever considers the merits of Langevin’s First Amendment claims.

What Happens Next

Now that the lawsuit has been filed, the legal process will move forward through several stages.

First, the City of Palm Bay will have an opportunity to respond to the lawsuit. The city’s attorneys will likely file a motion to dismiss, arguing that Langevin’s claims fail as a matter of law for the reasons discussed above. This motion will ask the judge to throw out the case without a trial.

The judge will then review both sides’ arguments and decide whether the lawsuit can proceed. If the judge grants the city’s motion to dismiss, the case will be over unless Langevin appeals. If the judge denies the motion, the case will move forward to the discovery phase, where both sides exchange documents and information.

If the case survives the motion to dismiss, there may be additional motions for summary judgment, where each side argues that the undisputed facts entitle them to win without a trial. Given the strong case law in the city’s favor, the city will likely seek summary judgment, arguing that even if all of Langevin’s factual claims are true, he still cannot win under the law.

If the case proceeds all the way to trial, a judge (not a jury, since this is a constitutional claim against a government entity) will hear evidence and make a final decision. However, most cases like this are resolved long before trial, either through dismissal, summary judgment, or settlement.

Throughout this process, the new council rules will likely remain in effect unless Langevin seeks and obtains a preliminary injunction-a court order temporarily blocking the rules while the lawsuit is pending. To get a preliminary injunction, Langevin would need to show that he is likely to win the case and that he will suffer irreparable harm if the rules remain in place during the litigation. A preliminary injunction is not likely to be granted in this case, because the lawsuit contains internal contradictions and strong prior court decisions that back the city’s authority to set meeting rules.

The entire process could take many months or even years, depending on how the case progresses and whether there are appeals.

Endnote: Key Cases Explained

Houston Community College System v. Wilson (2022): This case involved a community college board member who was censured (officially criticized) by his fellow board members for making critical comments about the college. He sued, claiming the censure violated his First Amendment rights. The Supreme Court agreed that he could sue for a declaration that his rights were violated and for an injunction to prevent future retaliation, but he could not seek money damages from the college. This case is important because it shows that elected officials have some First Amendment protections, but their ability to recover damages is very limited.

City of Newport v. Fact Concerts, Inc. (1981): This case established that cities cannot be required to pay punitive damages in civil rights lawsuits under Section 1983. The Supreme Court reasoned that punitive damages are meant to punish wrongdoers and deter future misconduct, but punishing a city would ultimately harm innocent taxpayers who had nothing to do with the violation. This case limits the financial liability of cities in civil rights cases.

Bogan v. Scott-Harris (1998): This case held that local legislators have absolute immunity from being sued for damages for their legislative acts. The Supreme Court explained that this immunity is necessary to protect the legislative process and allow elected officials to make decisions without fear of personal liability. Even if a law or resolution is later found to be unconstitutional, the legislators who voted for it cannot be sued personally. This case strongly protects the independence of local legislative bodies.

Together, these three cases create a legal framework that makes it very difficult for elected officials to sue their own legislative bodies over procedural rules or other legislative decisions. While the First Amendment does provide some protections, courts generally give wide deference to legislative bodies to manage their own internal affairs.

I find it incredulous that the same ones that want to circumvent others' rights and freedoms are so quick to sue and whine when they get called out on their BS. So quick to want to hide behind the constitution while only be so happy to violate others constitutional rights. Hypocrites

Thanks Tom. Informative documentation of the case law. The City Attorney made a similar compelling case (when pressed by the Mayor) based on Court cases at the Oct 16 meeting. I'd sum it up this way, its always a up-hill battle when you try to sue the Government. As a taxpayer, who lives in this City with a large influx of growth (that the City seems unable to monetize in lieu of property tax increases) I would think its in everybody's interest to settle this case, not go to the expense of litigating it. In his comments on this subject at the Oct 16th meeting, Councilman Langevin implied he would accept a Censure if he could speak at Council Reports. IMO it seems like that was the opportunity to compromise and prevent litigation. Going forward the voters can determine the future of the estranged Councilman. Another thing to keep in mind here, the Councilman is a easy figure to take a dim view of. If we are going to determine that the high bar of election nullification has been met, what happens next time if a quorum of the Council pursues nullifying another Council member on the same grounds? For example I recall a few years ago the Mayor submitted a Veteran for special recognition, turns out the individual had been dishonorably discharged. (I defended the Mayor btw) The media and many residents found this controversial. Some of the same arguments could be made here, it could be argued the Mayor put the full faith and credit of the City in a perceived bad light. (I don't recall a censure being discussed) There are many examples here, like the previous Mayor, some dubious accusations against Councilman Johnson, a Federal investigation into City practices etc. In those cases the voters dealt with the Council . The last time a councilman was removed, it was clear a crime had been committed. If we start muting Councilman for making jack-wagons of themselves, IMO we will all pay for it and its only a matter of time before your candidate gets gored.